|

We've gone over to WordPress. Come check out, like, and follow our new blog at www.delvewriters.com.

1 Comment

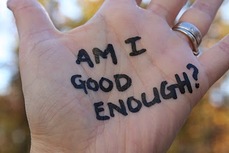

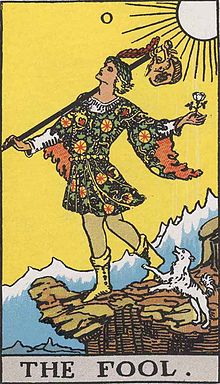

We've moved! This will be the final post on this blog site. New posts (including this one) can be found at delvewriters.com. Hope to see you and hear from you there!  Today is Friday the 13th, so you'd expect demons. And you'd be correct. The great state of Colorado --and home to Delve Writing-- is under siege again. After devastating wildfires, we now have torrential rains and formidable floods. Delve staffers are safe and mostly dry, but we're surrounded by friends, neighbors, and countrymen who are battling the rising waters, and in some cases swimming for their lives. There's 24-hour news coverage of disaster and destruction--stuff that's happening mere miles from my house, Facebook is brimming with posts from friends and acquaintances in affected areas, and my cell phone buzzes with an Emergency Alert every few minutes. Today was supposed to be a binge-day of editing for me, but I admit to finding it difficult to submerge myself in my story when so many around me are literally submerged.  In addition to my own personal Facebook demon, Davy Jones, sitting next to me, I also find myself battling the familiar demons of email and distraction, as well as the occasional call from Mabel & Ethel (the friendly ladies who volunteer their time as the telephone landline demons). Do these events constitute a genuine reason for not writing? Sure, if I wanted an excuse not to work on my manuscript, I'd say the events of this Friday the 13th provide a solid one. But honestly, my ducks are all safe, my house is dry, my power is on (and my computer has mostly recovered from The Great Iced Tea Spill of 2013), so there's really nothing preventing me from getting some editing done except for me and my personal demons. So how do I turn off the outside world and tune into my story? In the face of all the news flashes, flash floods, and flashy demons, my best defense is surprisingly the kitchen timer. My plan is to disconnect from media (social and otherwise), set the timer for one hour, then dive into my edits. When the timer beeps I'll summon my frenemy Davy Jones and together we'll check Facebook, the answering machine, and the local newsfeed.  Sound like a plan? If you're with me, grab your kitchen timer and strap on those water wings! And keep in mind the best advice --for writers and disaster victims alike-- in these words-to-live-by from the incomparable Dory: JUST KEEP SWIMMING. IMPORTANT NOTE: This blog is moving to www.delvewriters.com. We hope to see you there next week! They're Ba-ack! My writing demons have returned. Or have they? You see, the last couple months have been chock full of ducks, which gave my writing demons the perfect opportunity to swoop in and wreak havoc. And swoop and wreak they did, or so it appeared. Here's what happened: In the midst of a very chaotic summer, I sent my current work-in-progress out to "beta readers" as a sanity check of sorts before I submit the manuscript to two agents who requested it. When I sent it to the beta readers I felt pretty dang good about it. I knew it wasn't perfect, but I was spitting in the face of my perfectionist demon (sorry, Harpy), feeling confident the story and the writing were good. Perhaps even "good enough."  Then came back-to-school chaos, and I was so wrapped up taking care of ducks, I wasn't thinking about demons at all. I let my guard down. That's when I received the critiques from my beta readers. As an unpublished writer, even when my guard is UP I have a permanent chink in my armor where demons can slip in: I'm already always asking myself "Am I good enough?" This is the part of the story where the demons swoop in. Even though most of the beta readers' feedback was positive, a few tiny criticisms snowballed in my psyche. I began to feel like the manuscript SUCKED. Like the problems were insurmountable: too many, too varied, too widespread, too inherent--take your pick. I became certain I'd never be able to fix them. My story would never be "good enough," much less perfect. I could work for several more years on this book and still not even be close. "What's the use?" I thought. And I stopped working on my manuscript. After some wallowing I began to suspect I'd been victim to a sneak attack by the Demon Triumvirate: Insidious Sam (the demon of worry), Kakorr (the demon of fear), and Aunt Fay (the demon houseguest of fatalism).  THOMAS THOMAS But then I learned that Sam, Fay and Kakorr had been on Walk-About for the past month (long story--don't ask) and therefore could not be the guilty parties. Snickerdoodle, Vex, Davy Jones and the rest of the colorful lot are also accounted for, and my ducks are all squared away, too (if not in a neat row). So who's been sabotaging my manuscript submission efforts? Allow me to introduce Thomas, the demon of self-doubt. Thomas is not exactly a new demon. It's not like I've never felt self-doubt before. It's just that he's usually accompanied by a hoard of other demons who mask his appearance. Take Worry, for example. Self-doubt can often be an underlying element of worry. Same for Fear, Fatalism, Perfectionism. Even Procrastination and Distraction can have roots in self-doubt. When he's not lurking in the shadow of another demon, Thomas usually reveals himself by whispering subtle, seemingly helpful warnings: Don't wear that -- people will ridicule you. Better not go on stage -- you'll trip, say something stupid, or otherwise make a fool of yourself. You shouldn't write that -- it makes you sound naive and dumb. For goodness' sake, don't submit your manuscript to an agent -- you'll be a laughing stock. Getting published? Forget about it. Everyone will know you're a hack and a fraud. Obviously if I ever hope to finish editing my manuscript and submit it to the perhaps-no-longer-feeling-quite-so-patient agents, I must banish Thomas. But how? I've tried cigars, coffee, calamine lotion, reggae music, advice from my mentor, unplugging the phone, Post-It Notes, antacids, duct tape, dreamcatchers, nightlights, chamomile tea, and sticking my fingers in my ears. But none of these trusted demon-defenses work on Thomas.  BRUCE BRUCE Unless Bruce Willis is available to babysit me for the weekend, I'm at a serious loss. Please help me out here-- What do you use to banish self-doubt?  You may think "at the border without a passport" is a cute new way of saying "up the creek without a paddle" or "all dressed up and no place to go," but you'd be wrong. Last week I was actually at the Canadian border, trying to cross without a valid passport. Now that I think of it, that is the same thing as being up the creek without a paddle and all dressed up with no place to go. "How could you have gotten yourself into that unfortunate situation, and what does it have to do with writing?" you may be asking. Or you may be pointing at me and laughing while screeching, "You idiot!" (in which case you would not be alone). Given those two scenarios, I'm going to choose to believe you are not ridiculing me and calling me names, and I'll tell you the story of how this unfortunate situation came to be. And how it relates to writing. Which it does. I promise.  Once upon a time there was a writer who was also a very busy mom with two children preparing to go to school abroad. In recent weeks this writer-mom spent very little time writing and a whole lot of time ushering her children through the red tape of preparing to live in foreign countries, namely procuring the necessary legal travel documents. "Make sure you have your passport! You'd better apply for your student visa right now! Has that residence permit come through yet?" she could be heard yelling far and wide. (It was easy to hear her since there was absolutely no sound of tap, tap, tapping of fingers on keyboard to mask her voice.) She managed to get one son safely off to Sweden, complete with a nearly-impossible-to-obtain residence permit, and was on her way to deposit her second son at his university of choice in Canada, when the unthinkable occurred. While idling in the one-way, there's-no-way-to-exit line at the Peace Arch border crossing, she took out her own passport only to find it had expired. Three months ago. And there's no grace period. Back in the pre-9/11 days, this wouldn't have been a problem. But now? Problem. Big problem. In a little aside I'll tell you that this writer-mom is known to her friends and relatives as "the prepared one" (or behind her back: "the over-prepared one"). She's always got a safety pin handy, magically produces an aspirin just when you need it, and can provide a resource, reference, map or guide to anything at the drop of a hat. Her critique group calls her "Kanga" because it's like she always has a big pouch full of all the things you might need in any given circumstance, no matter how unexpected said circumstance might be.  So how, you may be wondering, could Miss Kanga have gotten herself in such a fix at the border? It's not like the trip was unexpected. It's not like she hadn't spent the last two months up to her neck in red tape of the entering-a-foreign-country variety. The how is actually very simple: It happened because I was so focused on what everyone else needed, I neglected to make sure I had what I needed. I mean She. Kanga. The writer-mom. The how of how this relates to writing is three-fold: 1. I neglect my writing because I'm so focused on taking care of other people and obligations. (Too obvious?) 2. Similarly I focus on developing my secondary characters to the neglect of my protagonist. And like me, my protagonist and my writing suffer as a result. (Not as obvious?) 3. I need to scrap the idea I had for a short story about an American citizen getting turned away at the Canadian border due to an expired passport. Because it wouldn't be credible. (Did you see that one coming?)  Yes, I crossed that border with the well-wishes of not one but two Canadian border patrol officers who either didn't notice or didn't care that my passport had expired. No one was more surprised than me. I'm soooo glad I did not attempt to sneak across by hiding in the back of the car amidst my son's luggage. I think having to face my sons with an expired passport --after having berated them loudly and endlessly about their travel documents-- is humiliation enough, thank you. Although a mom smuggling herself across the border in her son's dorm-bound luggage might make a better short story....  from Aaron Brown filling in for Chris Mandeville this week... The young man, intent on the lofty heights of his own potential, steps off a cliff and plunges into darkness... So begins the story of the Tarot and of the archetypal Hero's Journey. If you've read Christopher Vogler's The Writer's Journey, or the work of Joseph Campbell (on which it's based), you're probably familiar with the formula: First, we meet our hero in the Ordinary World. She receives a Call to Adventure, which she initially Refuses. Fate and/or her Mentor help change her mind and so she strides boldly into the darkness, where she must suffer many hardships and perils and ultimately make some Supreme Sacrifice before she can emerge with an Elixir. Raise your hand if you've heard this one before... (The Wizard of Oz, Star Wars, every big budget Hollywood movie produced in the last couple of decades, etc.) Now, here's my question: why is this such a powerful story? Why do we listen so eagerly and identify so readily with such a simple and endlessly repeated formula? Could it be that we recognize the pattern of it as the essential process of personal growth? What if we considered the Hero's Journey as our own necessary journey and took our cues appropriately? You might think this is just a writerly bit of nonsense. Seriously, who's calling anyone to adventure, any more? Surely the last great adventures died out when all the frontiers went away. Life now is just about work and relationships and paying bills, right?  I would argue that's not true at all. I think we're all called to adventure on a quite regular basis. It's just that the adventures are mostly internal. To establish the point, let me focus on just one small aspect of every writer's life: Feedback. Think of some bit of critique or feedback you've received on your writing in the last few weeks or months--specifically one that made you either say: "Ugh, that #$%@ imbecile had no idea what s/he was talking about," or "Yeah, yeah, I know that would make my work better, but I just can't commit the time or energy to do it right now." Any time you experience an exceedingly negative response to a piece of feedback, or respond with a "Yeah, but..." I would argue you've just received a potent Call to Adventure and Refused it. Steps One and Two on the Hero's Journey: check! The trouble is, most of us stop there. We neither trust fate nor a mentor enough to help us make the crucial decision to enter the darkness. Or perhaps we do plunge into a darkness of self-doubt and despair, but then fail to make the Supreme Sacrifice necessary to recover an Elixir.  So how do we proceed? What can we sacrifice without giving up our true self? How do we know what to change and what to preserve? After all, isn't it entirely possible that the person giving us feedback was in fact wrong? Or, even if the person might have been right, couldn't it be true that they're just right for other people? Don't all the great authors out there succeed by sticking to their guns and believing in their own work even when others don't? If I just write some book other people want to read, won't I be giving up the whole point of me becoming a writer in the first place--the opportunity to tell my unique and singular story? These are all key questions to ask when you're in the darkness. Indeed, I think it's only from asking these questions that we can find our way to the Elixir. The trick is minding our own internal antagonists along the way. Just as antagonists typically drive the early part of the action and propel a hero toward her destiny in fiction, so too can our own demons lead us toward the crucial moment when everything is on the line. Pay attention to where your own resistance is most intense. Where do you feel most tender? Most vulnerable? Most angry? Most frightened? What part of you are you desperately and even irrationally trying to protect, despite the fact that you keep receiving feedback that it's a weakness? Do you keep saying "Yeah, but..." or "You're an idiot!" when people approach this very sensitive spot? If so, that's likely the place you need to go if you want to find the Elixir. It may seem impossible or profoundly unpleasant, but I'm guessing the impossible-er or unpleasant-er it feels, the more important it is to push at that precise spot. You may feel brutally and wretchedly exposed or humiliated, or it may seem like all the work you've done for so long is suddenly worthless. You may feel alone, abandoned, sold out. Certainly this is the point we try to take our heroes to on their journeys. So why not follow them there ourselves? Just as it's true for our Heroes, at a certain point, it will all be up to you. You will be given the opportunity to learn the lesson, to sacrifice the precious thing you've been clutching, to face the most frightening enemy you can imagine and give everything you have to the encounter. Muster your courage, gather your conviction, and then let go. And don't forget to grab the elixir on your way out. [P.S. - Once you've returned (or to those who've already gone through that darkness), tell us in the comments what you found.]  It's Shark Week, and this time it's ACTUAL Shark Week, not a reference to my own editing "week." "Why do I care?" you might be asking. "What on earth does Shark Week have to do with writing?" "Plenty," I reply. "Let me count the ways." TEN THINGS WRITERS CAN LEARN FROM SHARK WEEK 1. Don't count your sharks before they're hatched: a two-headed baby shark was cut from the uterus of an adult shark. Lesson: you never know how many stories you have inside you. Sometimes you think you're gestating one, when it turns out there's a sequel attached. 2. Speaking of gestation, for the frilliest of sharks (aka the Frill shark), gestation can last 3.5 years. Lesson: for the frilliest of stories (aka complex, detailed and rich), gestation can take a lot longer than we're prepared to carry that story around inside of us, so be patient and allow enough time for the story to fully develop.  3. Basking sharks are the second largest shark, and they use their enormous mouths to gobble up not giant squid, but teeny-tiny plankton. Lesson: sometimes it's the small things that nourish us -- a smile from a reader, a compliment from a critic, a kind word in a crap-laden rejection letter -- so don't miss those crumbs because you're focused on taking the cake. Or the giant squid. 4. Thresher sharks attack with their tails, not their teeth. Lesson: attack your manuscript with whatever tools are at your disposal, not just the ones you're expected to use. 5. The Japanese Wobbegong shark is a weak swimmer who gets around by walking along the sea floor on its fins. Lesson: writers aren't the only weirdos on the planet. Embrace your weirdness and use it to get where you want to go. 6. The Greenland shark is one of the slowest moving fish, yet reindeer, polar bears and speedy seals have been found in their stomachs. Lesson: reindeer? Really? I guess slow and steady really does win the race.  7. Hammerhead sharks can see everything except what's right in front of their faces. Lesson: writers can see everything except what's right in front of our faces, so employ a critique group or partner to help you see what you're missing in your own manuscript, then do the same with theirs in return. 8. Most shark attacks on humans occur in shallow water. Lesson: don't just dip your toe in-- If you dive in with everything you've got, maybe you won't get eaten alive. 9. Sharks have thick skin to help protect them from the bites of other sharks, like the Cookiecutter Shark (yes, that's a real shark). Lesson: develop a thick skin to protect yourself from the biting words of other writers (and editors, agents, and critics), as well as from writing demons like the Snickerdoodle Demon (yes, that's a real demon! See A COMPENDIUM OF WRITING DEMONS if you don't believe me.) 10. Thanks to ecotourism, today sharks are worth more alive than dead. Lesson: your stories are worth a lot more when they're out in the world being viewed by others, so get them out there!  11. Expecting me to stop at ten? Eleven is my lucky number, so here's a bonus lesson: Don't be swallowed by the beast (or shark, or demon) of perfectionism -- As my mentor always says, perfect is the enemy of the good. So break free of the grip of perfectionism, make your manuscript good (not perfect) and throw it out into the deep blue. You'll never get any bites if you don't. In the spirit of full disclosure, I have not actually skinny-dipped with Neil Gaiman. However I find this phrase a quick way to reference an important writing lesson, which I'll share if you'll permit me the latitude to explain. Also in the spirit of full disclosure for those of you keeping track, I only achieved 2 of the 5 writing goals I set this week. In a moment I think you'll understand why. My son was due to get on a plane last Saturday to spend a year studying in Sweden, but as of one week prior he still didn’t have the requisite Residence Permit. Everyone involved was sure he’d have to forfeit his ticket and reschedule his trip, but I wasn't ready to give up. So I spent last week relentlessly phoning, emailing, and faxing the Swedish Embassy, and to everyone's surprise (even my own) managed to secure my son's permit 24 hours before his flight. Lesson Part One: PERSEVERANCE PAYS OFF Or at least it can pay off when applied properly. In my case I did not apply it to my writing, thus only completing 2 of my 5 writing goals this week.

So, what does this have to do with Neil Gaiman? The easy answer would be that I found a quote from him about perseverance, but if you bet on that you just lost your lunch money because what I found wasn't about perseverance at all. What I found was this: "The moment that you feel that just possibly you are walking down the street naked... that's the moment you may be starting to get it right." Neil Gaiman I sure don't like feeling (or being) naked in public, but "getting it right" as a writer is what I live for. It's right up there with family and coffee. It's what I strive for each time I sit down to work on a manuscript. Which brings us to: Lesson Part Two: TO WRITE THE GOOD STUFF, YOU MUST EXPOSE YOURSELF Of course I'm talking about feeling vulnerable and exposed due to putting authentic, personal thoughts, emotions and fears on the page, so don't take this as license to become a flasher. And finally, the Finding Nemo connection. As I slogged bleary-eyed through multiple phone mazes in Swedish (which I don't speak), and then later as I searched the Web (in English) for writing quotes about perseverance, I kept hearing this little voice in the back of my head. And thus we arrive at: Lesson Part 1 + Lesson Part 2 = TO WRITE THE GOOD STUFF, YOU MUST EXPOSE YOURSELF OVER AND OVER -- JUST KEEP SWIMMING, JUST KEEP SWIMMING -- AND IF YOU'RE FEELING NAKED, NEIL GAIMAN SAYS YOU MAY BE STARTING TO GET IT RIGHT Which is a really wordy lesson to carry around in your writer's toolbox. Believe me, I tried. So I hope you'll forgive me the somewhat misleading headline "Skinny-dipping with Neil Gaiman" and allow that it's a much pithier (and easier to hum) mantra. Now if you'll excuse me, I'm swimming my naked self over to my manuscript -- I'm down by 3 goals, and I'm determined not to let the Swedish Embassy team win this one.  The thing about ducks and demons is, they can be difficult to tell apart. Yes, I know, some are more cute and cuddly than others. But when it comes to achieving my writing goals, they both do an impressive job getting in the way. This past week I set extremely unambitious goals because I expected life to get in the way. I just didn't expect it to BLOCK the way. Life, the universe, or something put up a ginormous roadblock that prevented me from making a single iota of progress on my novel. I confronted that hulking roadblock, daring it to declare itself: Duck or Demon? "Ducks" are those responsibilities I feel obligated to attend to: family stuff, house stuff, health stuff, etc. I try to keep them all in a nice orderly row so that my life runs smoothly and I can accomplish everything I want to accomplish, including my writing. "Demons" are nuisances, distractions, deterrents and temptations that get in the way of writing and threaten to derail me from achieving my goals.  If I told you that my roadblock involved the Swedish Embassy and oral surgery, you'd probably say, "No question: DEMON." But hold the phone. You're jumping to conclusions based on your knowledge of the anguish typically experienced when encountering bureaucracy and high-powered dental tools. I agree they're unpleasant, unpopular and unforgiving, but that doesn't necessarily make them demons. At least not writing demons. As I stared at the massive, oozing roadblock in front of me, trying to figure out a way around, across or through it, I had some time to think. So I pondered for awhile the real difference between my ducks and my demons....and I concluded: The difference is my attitude. What I mean to say is, when a demon gets in my way, I know I'm supposed to get rid of him. I don't always make that choice, like when it comes to eMal or Davy Jones (the Demon of Facebook), but that's beside the point. The fact is, demons should be banished. I know that and you know that. It might as well be law. But ducks? They have every right to be there. Family. Friends. Chores. Errands. Appointments. Even taxes. We don't get rid of them (at least not usually). We can't. They're obligations. Responsibilities. Facts of life. We don't always like them, but we accept them. We have to. Again, law. So back to my colossal roadblock of Embassy red tape and wisdom tooth extraction-- Do I have a new demon?  Oh, did I mention that the international imbroglio and repeated visits to the oral surgeon's office were made possible courtesy of my teenaged sons? Family obligation. Duty. Responsibility. Ducks. Clearly ducks. And if it quacks like a duck, well, you know what I did. I treated that roadblock like one giant duck. The truth is, I'd have been better off if it had been a demon. Why? Because then I would have at least tried to write. Instead I paced back and forth in front of the roadblock, clenching my teeth to keep from cursing obscenities. (If you must know, it's possible an obscenity or two slipped out.) I accepted without question that I had to take care of my son's apparently-impossible-to-obtain-in-a-timely-manner Student Visa and my other son's quadruple wisdom tooth extractions, complete with the requisite buying of ice cream, and the mandatory making and delivering of milkshakes. Of course I had to take care of those things. I'm not saying I didn't. So what am I saying? That I used them as an excuse not to even try to work on my novel. There. I admitted it. I could probably have gotten at least a tiny bit of writing done if I'd tried. But I didn't try. I called a duck a duck and I treated it as such. Had I just called it a demon.... Who knows what I might have accomplished? So next time you face a writing roadblock, ask yourself: I say it's in the eye of the beholder. And I also say:

Don't be afraid to put on your demon-colored glasses. Right now I'm in the throes of a final editing pass (or two) before sending my manuscript to two agents who requested it. If you read my post from two weeks ago, you may be a bit confused by the fact that I'm still editing, given I referred to last week as "Editing Week." Rest assured, I never believed I'd be done in one week. I just thought "Editing Week" had a nice ring, like Shark Week. But we all know that, despite what we see on TV, those sharp-toothed predators prowl the seas every week of the year. Go ahead, carry that analogy over to editing. So yes, I'm still submerged in the deep, dark sea of editing, battling my sharp-toothed demons, and I will be for a bit longer, despite the cute "Editing Week" moniker. Anyone want to know what I'm doing down here in the deep? I thought I'd share a bit for your voyeuristic enjoyment, and perhaps even a little learning pleasure. Here goes.

How did you react in a moment when you were utterly helpless? To get the most out of the answer to questions like this, David prompted us to relive the scene, right down to what we were wearing, who was with us, what the weather was like, and what we said and felt. Delving into your past can be painful! But David didn't push us to do it because he's a sadist (he may be one--I have no personal knowledge one way or the other--but this isn't the reason he gave). The reason for a writer to do this kind of "work" (and make no mistake, it is work) is to bring authenticity to our characters. Reflecting on how you reacted in your most helpless moment can shed fourteen suns worth of light on what your character would do, why he'd do it, how he'd do it, and what he'd feel and think while doing it.  Skipping right past the memory of the moment when *I* felt most helpless, I'll share what this moment was for Reid, the main character in my work-in-progress, a post-apocalyptic New Adult novel, SEEDS: As a little boy he secretly watched as his mother was euthanized against her will. This event shapes Reid's life from that moment forward. For example, he becomes a medic to help others, and refuses to commit euthanasia even in the face of severe punishment. That right there gave me a lot to think about. But it was a different question posed by David that shone a spotlight into my character's core: What is your greatest moment of guilt?  It turns out, this moment of guilt is Reid's defining moment. It provides the internal motivation for pivotal decisions in the plot. It explains why in the end he does something that would otherwise make no sense to us. What, you want to know what that moment of guilt is? Okay, here's Reid's guilty moment: When Reid was nine, he had the chicken pox and was quarantined with a ten-year-old girl, Kayla, who stole his heart. It was just the two of them, laughing and telling stories to distract each other from scratching. Despite the itching, it was the best time of Reid's young life. That is, right up until his older brother Brian came down with chicken pox, and Kayla fell head over heels for Brian. Reid wished Brian were dead so he could have Kayla to himself. Then when Brian developed complications and nearly died, Reid felt responsible. He promised Brian that if he lived he could have Kayla. Brian recovered, but Reid never did. He still carries that guilt, even when intellectually he knows better. He's never stopped loving Kayla, but he's never broken his promise to Brian. Not even when Brian dies leaving behind his pregnant young bride -- you guessed it -- Kayla. Exposing my characters and my story here has made me feel sufficiently vulnerable that I'll leave it to your imagination what my personal guilty and helpless moments were that led to these character revelations. But you get the idea, right? So, writers, ask yourselves: When was I most sad, ashamed, or afraid? Then, David suggests, look at the converse of that moment: What was my golden moment, when I was most joyful? Or most proud? Or most brave? Now imagine your character experiencing those opposite emotions, and draw a line connecting them: How does the character get from anguish to joy? From fear to courage? From pride to shame? By taking opposite emotional gems -- mined from your own life -- you can create a character arc. Jiminy, that's enough right there to keep me revising into next year. But that's not all David shared, not by a long shot. What really struck me during David's workshop was the offhanded comment: "We are all trying to create, maintain, or defend a way of life." Now that got me thinking. Not just about how chock-full of great writing knowledge David must be to effortlessly discard such insightful bits of wisdom, but about how this particular bit of wisdom applies to my character: You see, Reid lives in a barren, post-apocalyptic world where nothing will grow. He doesn't believe any other way of life is possible, so he dedicates his life as a medic to keeping people alive. Maintaining.  He still feels this way when he and Kayla are banished from their community in Cheyenne Mountain. Here's an excerpt: The city below was brown and silent and still. Reid couldn’t imagine it any other way. He’d never shared his brother Brian’s conviction that the world would be reborn and green again. Kayla had. He wondered if she still did, now that Brian was gone. But then Reid and Kayla meet the first stranger they've ever seen, and she has an apple. This is the moment when everything changes for Reid. Now he knows that there's grown food in the world. He has hope that his people won't starve, hope that the world will be green again. After he sees the apple, he will never be the same, never look at the world in the same way again. I knew this about Reid before I attended David's workshop, but now I see it a little differently: In this pivotal moment, Reid goes from being someone who's trying to maintain a way of life to someone who's trying to create a new one. Don't even get me started on Reid's enemies. Thanks to David, I see them with fresh eyes now, too: One is busy provoking the community to defend their dysfunctional way of life against fabricated "Raiders," while the other is out to create his own way of life that runs counter to what Reid wants ... Or does it?  Wow, I've got lots to think about, lots to work out, and lots more editing to do. What about you? Are you intrigued by these concepts? Do you see your characters in a new light now? Are you flashing back to memories that suddenly appear to be studded with gems for mining? To learn more, check out David's book, THE ART OF CHARACTER, visit his site at http://www.davidcorbett.com, and head over to the "Recordings" section of Delve Writing where you can listen to David's 2-hour workshop completely free. Or click here if you can't wait another moment and want to watch the recording now. NOTE: Aaron Brown is Guest Blogging for Chris this week while she's on vacation. The following is something I shared with my Delve Check-In on Tuesday, which I'm hoping will have some value for more than just writers who happen to come across it. Cheers! "What we have to be is what we are." -Thomas Merton  I believe the wisdom we need to live our best possible lives is everywhere abundant. We're not starving for truth, we're drowning in it. After all, we humans have been pouring out our stories of victory and tragedy, heartbreak and epiphany for thousands upon thousands of generations. Surely those brackish waters contain more than a little of the good stuff. The trick (perhaps) is to catch hold of a sufficiently buoyant bit of flotsam and a favorable current and then flow with it. In other words, find a program that strikes you as true enough and right enough, and follow it to the best of your ability (rather than circling endlessly in a search for perfect wisdom, until you sink from perfect exhaustion). I've been trying to do this ever since I was given the quote from Thomas Merton printed at the top of this post. "What we have to be is what we are." That little bit of wisdom struck me as so simple and so right. Give your gifts. Do what is in you to do. Become what you are. What if that's really it? The whole show? Wouldn't that be grand? Since being given that little gem, I have: 1) seen the same advice printed at least a hundred different ways from a hundred different authors (thus affirming for me that it's worth heeding), and 2) realized it's a bit harder than it sounds.  So, I've augmented the quote a little with other sources I've stumbled upon and turned it into a 3-step program, one I've been trying to follow for the last several years. I have to warn you though, I'm by no means an expert or a perfect success story, though I do think the program is working. My journey has taken me from frustrated wanna-be writer/teacher/entrepreneur stuck in a numbing job to someone happily running a couple of small online teaching businesses, including one about writing, with a first novel on the way to print at the end of this year. That said, each month can still be a struggle to make ends meet and the road has been anything but smooth. So...grab your grain of salt (or even a whole salt lick) and take this for whatever it's worth to you. (And please feel free to tell me in the comments if you agree or disagree with any of the following.)  Step 1: Do what you can't help doing (that also creates useful beauty) The most common push-back I've heard to the idea of "becoming what you are" typically falls in at least one of three categories. a) I don't have any worthwhile natural gifts or useful talents (or I don't know what they are) b) What I want to do doesn't pay well (or at all) c) Too many other people are trying to do what I want to do, so I could never be successful My response to the first of those concerns is to focus on the "useful beauty" part. By "useful," I mean that someone else can get some kind of enjoyment, value or help from something you do or create. If there's anything you find yourself doing often and with ease that proves helpful to others in your life, then you have a gift to give. If you tend to do it well enough or efficiently enough that your contribution has at least a little sparkle of artistry to it--something unique that sets it apart from when others do the same task more grudgingly or with less joy--than you've got the capacity to bring more beauty into this world. I'd even say you have the responsibility to do so. To my thinking, beauty comes in endless variety, and has far less to do with aesthetic considerations than with the quality of workmanship. A spreadsheet or wooden spoon can be just as beautiful as a sonnet or silver dish when made by a master. As to the money and competitor considerations, I think there are a million creative ways to fit your calling to a vocation and if you follow the next two steps, after a certain point the money and competition won't matter, except insofar as they spur you toward further and further creations of useful beauty.  Step 2: Do it for 10,000 hours and then do it some more This is where things get both incredibly difficult and blissfully simple. If you've never heard of the 10,000 hour rule, a quick internet search will give you troves of studies and elegies extolling the notion that greatness only comes after a certain amount of dedicated practice. I first learned about it in Malcolm Gladwell's Outliers, and commend that book to you. Of course, this rule is tremendously hard not only because it's a heckuva lot of work but also because we're so well-trained in this culture to want rapid results. Many of us quit when we don't hit it big right away or when we bet everything on the hope of "making it" in six months or a year and then fall flat because we haven't put in our time. So, put in the time. 10,000 hours = 5 years of 40-hr workweeks; 10 years if you're putting in 4 hours a day, 5 days a week; or (obviously) much longer if you're putting in much less. But here's where the simple part comes in. Knowing it's going to take a while, you're free to let go of the pressure to perform. Just drop that weight from your shoulders like the useless burden it is. You don't have to be perfect. You don't even have to be all that good. You simply have to commit the time. Don't expect success at the start. That expectation will wreck you. Prepare for a long haul. If you can learn on someone else's dime, doing something at least similar to what you ultimately want to do, grab that opportunity like the gold it is, and remind yourself you're fulfilling your call simply by moving closer to it. Take pleasure in your progress. I also find it helpful--particularly when I'm wishing the world could just give me the money and time I need to focus on my art--to think about how many lottery winners have gone on to become brilliant writers or craftsmen or creators of any sort. Maybe there are a few, but I haven't heard of them. And yet, I'm willing to bet many of those winners had similar thoughts to mine before they hit their numbers. Oh, if only I had millions, I would just do X. But then they don't seem to do X when they get the millions. Are they all just talentless hacks cursed by a complete lack of inborn skill? Or is the struggle part of the secret? Is the challenge of finding ways to build your talent over 10,000 hours part of what makes you ultimately successful? I think it must be. In addition, the more we can focus on doing the things that do arise from the gifts we have, the less those hours will seem a chore. Indeed, they may start to seem a lot more like pure joy. By my rough calculations, I've got about 9,000 hours in on my writing, 10,000+ hours of teaching, and 8,000 of entrepreneuring. I haven't quite hit all my marks yet, but every day gets better and clearer and more rewarding as I try to bring these 3 callings into some kind of alignment.  Step 3: Remember, it's a gift Particularly during the 10,000 hours, it's easy to get greedy about our gifts, but it helps to remember they came to us unbidden. We have in us a capacity to do certain things better and with more beauty than others can do them. That's not something we earned. It's something we were simply given. That's a thing to be grateful for, not greedy about. During the 10,000 hours (and beyond) our job is to give back. The primary reward can and should be the satisfaction of aligning with our essential selves. The output is for someone else. Yes, we need money also, and we will likely struggle to earn that, but the gift and the giving of the gift should remain as unencumbered by our grasping as possible. The great thing is: the more we let go of the need to get something from our giving, the more we tend to actually get. There's another way in which this reminder about "the gift" is useful. I've known plenty of people who are working their 10,000 hours but, in my opinion at least, largely wasting them. They do so by clinging to the notion that their talent is for them. I think it's a reaction against the harshness of criticism and of exposing your gift before you've mastered it. And because it's true we can go too far when taking others' critiques to heart (some of which will undeniably be flawed), some people convince themselves to shut out critiques altogether. The trouble with this is, if you ever want to receive a fair return on the talent you bring to the world, it has to prove valuable to others who will be the ones giving you something for it. The selfish gift giver only gives people things they themselves want. These gifts, no matter how elaborate or expensive or fine, fail to delight their recipients. On the other hand, the person who listens--truly and deeply--to the desires and longings of others can give the simplest of gifts and those gifts will become the most treasured of all. This doesn't mean you should try to adapt your talent to serve everybody all the time. That's another sure recipe for failure. But it does mean you should find those who long for what you have to give and listen to them; learn from them; honor them. Take them as your teachers as you do your 10,000 hours and more. Those to whom you give in this spirit, will eventually return to you the greatest gift imaginable: the gift of fully becoming that which you are. |

AuthorChris Mandeville is the president of Delve Writing and a writer of "new adult" novels and a non-fiction project for writers. Archives

September 2013

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed